Ecne: Automated Verification of ZK Circuits

May 12, 2022

Ecne: Automated Verification of ZK Circuits

We present Ecne, the first verifier for testing R1CS soundness.

Prelude: Contextualizing the Project

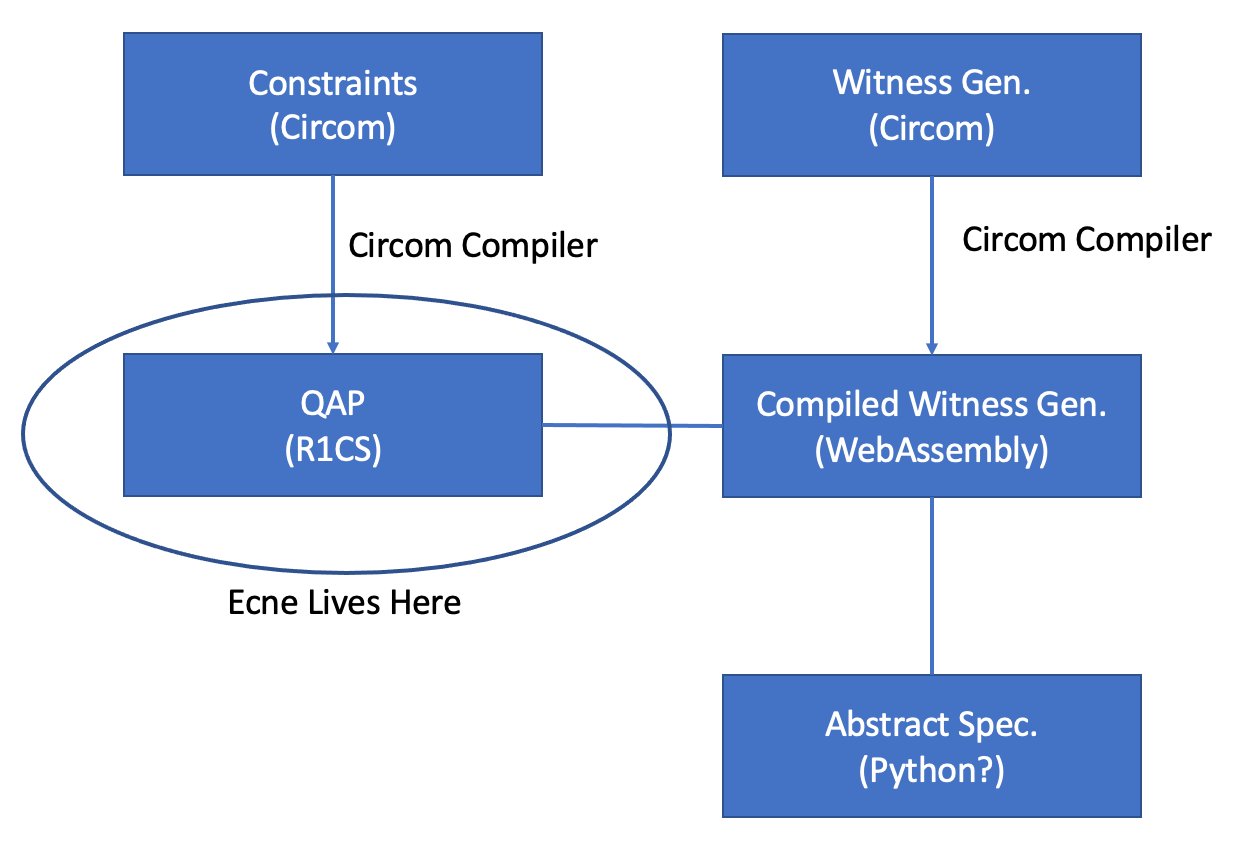

First, we give a brief overview of the Circom and Snarkjs zk-SNARK compilation toolchains.

The central object of a zk-SNARK is a function .r1cs file). The witness generation program in circom is converted to WebAssembly code, so that it can be run at proof time.

We would like to make various claims about the R1CS/QAP in relation to an abstract specification of the function we seek to implement (for example, an abstract specification may be

Motivation

At a high level, the first step in a zk-SNARK is converting standard functions (in the sense of computer science) into a quadratic-arithmetic program, a system of equations in the following form.

This conversion is useful because the conversion preserves the properties of the function, and QAPs are particularly amenable to zero-knowledge proofs with elliptic curve pairings.

To this end, QAPs play a crucial role in the Groth16 proving system and are widely used in many zk-SNARK proving systems.

QAP examples

First, consider a simple example, the function

For a slightly more nontrivial example, consider a program that indexes an array at a variable position -- in order to express this in QAP form, we'd use the following conversion.

To see why this works, observe that

Significance

One major difficulty with zk-SNARK development is that the conversion of a function into an QAP is a manual and very time consuming process, and if a constraint is missing it leads to the zk-SNARK becoming invalid and potentially hackable. To underscore the importance of this problem, note that function-to-QAP conversion is the only manual step in the process of creating a zk-SNARK.

Ecne addresses this issue by verifying that a given set of QAP constraints uniquely identifies a solution by operating on the QAP directly.

Goals of Ecne

There are several things we might hope for when checking the correctness of a conversion between a function and an QAP. We define the following terms:

- Weak Verification: This tests if, given the input variables in a QAP, the output variables have uniquely determined values.

- Witness Verification: This tests if all the witness variables that appear in all equations, and not just input and output variables, collectively are uniquely determined.

- Strong Verification: This tests if the QAP is exactly equivalent to a formal mathematical specification. For a function like "multiply two BigIntegers", this could be useful, because there's a specific specification we want to compute (multiplication). This one is the most similar to formal verification.

Ecne is primarily used to establish weak verification and witness verification (sometimes when assuming weak / strong verification of smaller circuit subcomponents), but in the future it could be extended to help establish strong verification as well.

Why weak verification and witness verification?

It may not be immediately clear why we should care about weak verification and witness verification. While these are natural concepts, what guarantees do they give us about our circuits?

Firstly, these notions of verification ensure that our circuits are not underconstrained. An underconstrained circuit admits valid proofs for multiple different outputs, given the same input. In the worst case, an attacker can generate a valid proof for an underconstrained circuit for any output--meaning that an attacker would be able to convince a verifier who (incorrectly) believes the circuit to be properly-constrained that the attacker knows the pre-image of arbitrary outputs. This is a severe security issue: a privacy-preserving digital currency system based on underconstrained circuits would allow an attacker to withdraw other people's money. Weak verification at least ensures that such attacks are not possible.

Secondly, weak verification and witness verification, in combination with testing of witness satisfaction, can help us build confidence in the equivalence of the QAP with an abstract function specification.

Let

Taking a bird's eye view, we are trying to show that, for all

Weak verification of

In conclusion, if a QAP

Thus, if we have weak verification and witness satisfaction for all

Witness satisfaction is hard to prove (see the limitations at the end), but one benefit is that since we already specify a witness generation procedure, we can repeatedly generate

Ecne Example

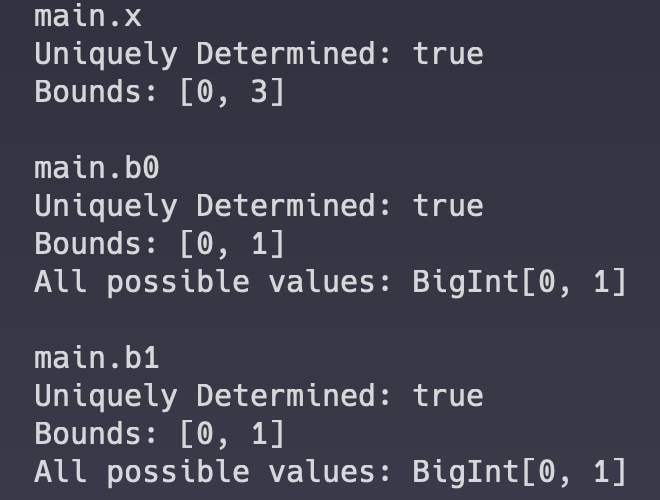

Consider the following constraint system, which implements the Num2Bits functionality for

This yields a unique solution for

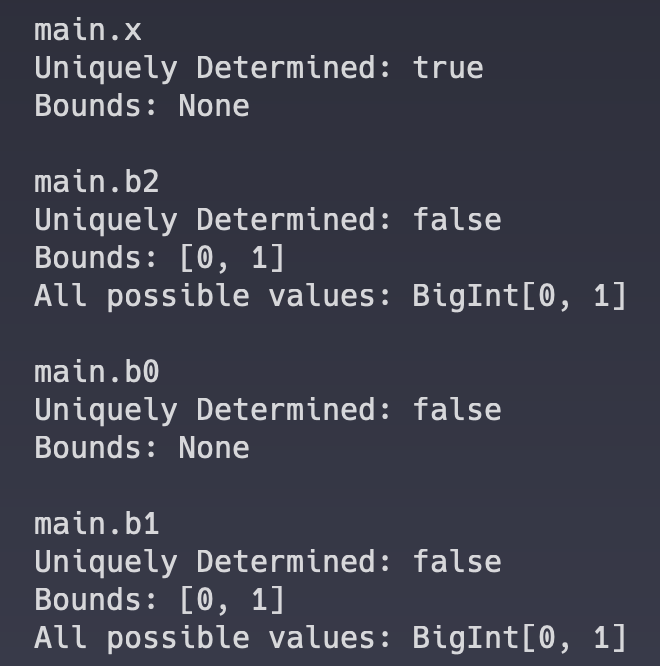

Now, consider a case in which we don't constrain

Here, Ecne will tell you that, while

Ecne will print this type of data out for every single variable, which can be helpful if you want to figure out where the equations first go awry.

Ecne Technical Details

Ecne follows a rule-based system and, at any given point in execution, maintains and updates a set of information about each variable in the system of equations. In the course of the algorithm's execution, we apply various inference rules to update variable states. These rules and the variable state schema are described below.

State Information

index: An identifier for the variable;

, if this is variable . unique: Whether we have proven that this variable is uniquely determined given the currently known variables.

lb (optional): A provable lower bound on this variable.

ub (optional): A provable upper bound on this variable.

values (optional): A set of possible values that we can prove this variable must be contained within.

abz (optional): A special field--a pointer

for which, if referenced variable is not equal to a specific value (which is different across all numbers which have ), then . As an example for why this field is useful, consider a system of equations Then the

of each of is given by the index of , because is zero as long as is not zero, is zero as long as is not one, etc.

Inference Rules

Then, we need to produce a set of rules to use while solving the equation. Here are a few examples of rules; our appendix at the end lists all inference rules.

- If all variables belong to one ABZ group and have a known sum, and the abz variable is known (so in the above, if we knew that

's value was uniquely determined and that ) then have uniquely determined values. - If

, and , and (and , where is the prime of the finite field (i.e. the BabyJubJub prime) then as long as is uniquely determined, are uniquely determined too. - If

, where is a constant square matrix with nonzero determinant, and is a uniquely determined vector, then is uniquely determined as well.

Rule-Following Algorithm

Most of the rules can be inferred with a single equation (as seen above, the first and second rules depend only on VariableStates and a single equation afterwards). This suggests an algorithm of:

- Try each rule on each equation over and over again, and stop when no progress is made.

However, this algorithm is slow, because it fails to exploit the fact that if no progress has been made on any of the variables in the equation, then there's no point in considering that equation again. Thus, we use the algorithm

Begin: Enqueue all equations that one can make progress on (generally, ones with few unknown variables)

Step: Given an equation, attempt to apply all of the rules to it. If progress is made on any variable, enqueue all equations with that variable.

The benefit of this algorithm is that we can bound the number of times any equation is enqueued. An equation in, say,

Then if all output variables are uniquely determined, we obtain weak verification. If all intermediate variables total are uniquely determined, we obtain witness verification.

Prior Knowledge

There are certain claims that we cannot easily resolve with the methods described above. To give an explicit example, say that we had equations which established that (in base

Combined, these conditions indicate that if

This then begs the question: How do we represent information like the equations above? For this, we'll need a trick: Trusted Functions.

Suppose we know that a function is strongly verified. Strongly verified functions are (so far) all verified by hand -- the functionality for strongly verifying functions programmatically would require a theorem prover. However, strong verification is needed if we want to use mathematical properties of functions to make deductions like above.

After strongly verifying a function, we compile it to an R1CS. Then, we run what is an essentailly a find-and-replace for that function inside another R1CS. For example, the following circuit constrains the isZero function (i.e.

If within another R1CS we see the constraints

then we can safely fold these constraints into

Now, we have an R1CS along with some special constraints that look like

In practice, this means that you can feed trusted R1CS to the solver to help the prover show weak verification of an untrusted R1CS.

Results

Applying Ecne, we have been able to weakly verify 49/72 of the functions in circomlib. Most of the other circuits pertain to elliptic curves, and are likely much more challenging to weakly verify without far more mathematical tricks -- in addition, some circuits, like the BabyAdd function, do not have formally stated preconditions, meaning that they are impossible to verify by themselves. [2]

With these techniques, we are able to weakly verify the unaudited v0.0.0 ECDSAPrivToPub circuit (a complicated circuit with over

This was actually useful in practice, because when verifying ECDSAPrivToPub we knew to just focus on each of BigMultModP and BigLessThan, and BigMod (a subroutine of BigMultModP) was lacking a range check. Fixed here.

We also considered two of the most widely deployed circuits, namely Polygon Hermez and TornadoCash.

- For the case of TornadoCash, we are able to obtain witness verification* of the withdraw circuit.

- In the case of Polygon Hermez, we are able to obtain witness verification* of withdraw and weak verification* of rollup-main.

The asterisk is explained in the section on partial functions.

Limitations of Ecne

Ecne is a tool for showing weak / witness verification, but there is still a gap between what Ecne can prove and what it takes to have full confidence in our circuits. Here, we describe some of the limitations.

What if Ecne can't show weak / witness verification?

There exist QAPs for which Ecne cannot prove weak or witness verification, but whose outputs are indeed uniquely determined by inputs. Oftentimes this is because Ecne does not have enough inference rules to prove that the system of equations has a unique solution for either the witness or output. For example, the BabyAdd circuit from circomlib (even with preconditions) is not within the scope of Ecne to weakly verify, because it requires very complicated mathematical reasoning to prove--specifically Theorem 3.3 of this paper.

Note that when Ecne does terminate with a positive result, we can be confident in the weak verification. In other words, Ecne will never indicate that an underconstrained circuit is indeed weakly verified, though for some circuits that are indeed properly constrained, Ecne may be unable to perform weak verification.

OK, now suppose that we do have weak verification. We showed earlier that weak verification, combined with witness satisfaction, was enough to prove equivalence. How might witness satisfaction fail? There are two main reasons: there could be bugs in the witness generation process, or

Errors in the witness generation process

It could be the case that the witness generation procedure does not always create

Partial Functions

It could also be the case that the witness generation procedure does not create

These functions

One way this plays out is that we may think that we have solved for a value of

For a more practical example, consider a function

If I had the QAP

Roadmap and Future Directions

What lies ahead? A few things:

- Some QAPs in the pipeline use methods in which witness verification does not hold (by design), but eventually lead to uniquely determined outputs; these may be slightly beyond what we can verify currently.

- General performance improvements.

- More practical examples like TornadoCash and Hermez. If you're interested in running Ecne on your circuits, please reach out to us!

Acknowldgements

This work would not be possible without several people, who I thank here.

- Thanks to gubsheep for helping with many drafts of this document, and to Yi Sun, Wen-Ding Li, and the rest of the 0xPARC community for many helpful suggestions.

- Thanks to Antonio de la Piedra for many helpful pull requests.

- Thanks to Andrew Sutherland for showing me websites that contain formal verifications of elliptic curve rules.

Appendix: All Rules

- (Rule 1) If

, and is a constant, then is also uniquely determined. - (Rule 2a) If

, then . Namely, if , then as well. - (Rule 2b) If

, then . - (Rule 3) If

, and are all in , then . Furthermore, if is uniquely determined, so are . - (Rule 4a) If

, then all properties from are copied to . - (Rule 4b) If

, and (or ), then the other variable is also in . Furthermore, if is uniquely determined, is uniquely determined as well. - (Rule 5) If

, and , and (and is less than , where is the prime of the finite field), then one can bound similarly to Rule 3, and if is uniquely determined, then are also uniquely determined. - (Rule 6) This is a rule called the AllButOneZero rule, and is described in the main text.

- (Rule 7) If

, where is a constant square matrix with nonzero determinant, and is a uniquely determined vector, then is uniquely determined as well.

A somewhat unexpected property of the above procedure is that in its current incarnation, it often depends on using unoptimized R1CS (compiled with O0) instead of R1CS, because only then can the find-and-replace can work -- otherwise, the constraints in a R1CS that computes a function which uses

as a subroutine may not include the exact constraints for as a substring due to various optimizations. ↩︎ Websites like http://hyperelliptic.org/EFD/g1p/auto-twisted.html contain some level of verification of elliptic curve group laws, which serve as evidence that verification of ZK circuits for elliptic curve operations is likely tractable. ↩︎