ZK Identity: Why and How (Part 2)

April 27, 2022

ZK Identity: Why and How (Part 2)

by gubsheep

A series on why new advances in cryptography may be important for digital identity primitives. The first post covers the “Why”; this post covers the “How.”

In our last post, we discussed why new cryptographic tools, such as zkSNARKs, will be crucial for constructing the next generation of digital identity infrastructure. In this post, we’ll dive into the weeds—what technical work needs to happen to build proof-of-concept ZK-based identity systems?

The ZK Identity “megaproject” is much larger than any one organization. Setting standards, building infrastructure, and iterating on identity primitives and application design questions will happen gradually, and require input from a variety of different stakeholders and areas of expertise. Given that ZK identity mechanisms have the potential to impact many people and also to rely heavily on public goods—open-source infra, tooling, standards, coordination—it is important that the effort arises bottom-up from an organic and community-driven “ecosystem,” rather than top-down from a single company; and that special attention is paid to sustainable development and incentive design.

It is also increasingly unlikely that an isolated company will succeed in such a dynamic ecosystem, as technology developed independently at all levels of the stack is changing rapidly. Instead, we’ll need to foster and coordinate an ecosystem of modular, fast-moving, and semi-independent teams sharing a common overall vision.

The 0xPARC ZK-identity working group hopes to contribute to the collective ZKID effort where we can, and we invite others who are actively thinking about this problem to join us and compare notes.

Building Blocks for ZK Identity

ZK Identity tools must enable participants in digital systems to make claims about identity and reputation. Concretely, these claims boil down to mathematical statements about the execution of cryptographic operations like signature verification, key generation, hashing, and encryption in zero-knowledge. We can combine these “building blocks” together to build ZKPs for more complex claims: for a toy example, see our post on ZK Group Signatures.

Some operations and cryptographic schemes can be implemented more efficiently in zkSNARKs than others. In the long term, SNARK-friendly cryptographic standards may be adopted by new identity providers that don’t yet exist today—for example, blockchains with public/private key signature schemes based on SNARK-friendly cryptography (or more expressive systems like account abstraction). But in order to prove concept and to be useful in the near term, our tools need to integrate cleanly with existing cryptographic identity systems—for example, Ethereum’s present ECDSA signature scheme, or more recent cryptographic standards coalescing around pairing-friendly elliptic curves in other contexts.

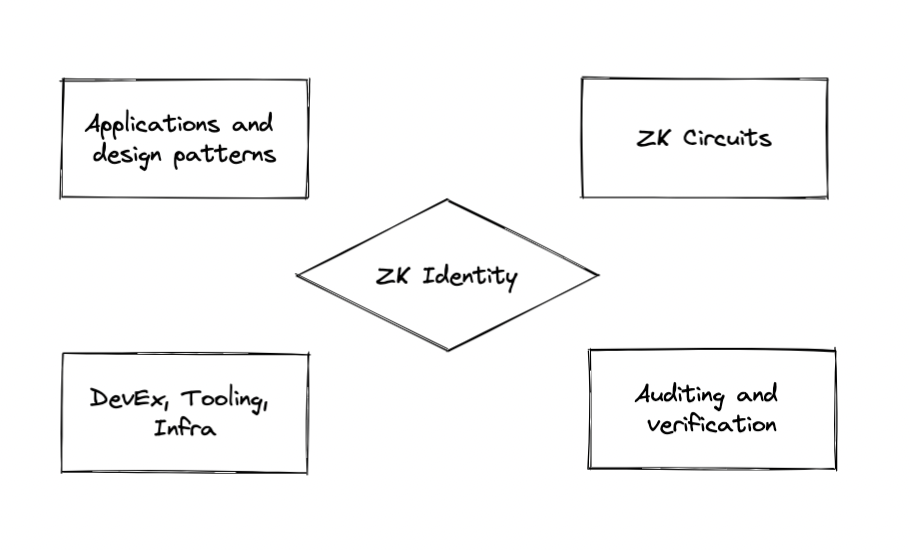

We believe that building a usable toolstack for ZK Identity applications will require significant progress on four fronts: ZK application design patterns, implementation of ZK circuits for cryptographic primitives, circuit security tools, and developer tools and infrastructure. We summarize each area below.

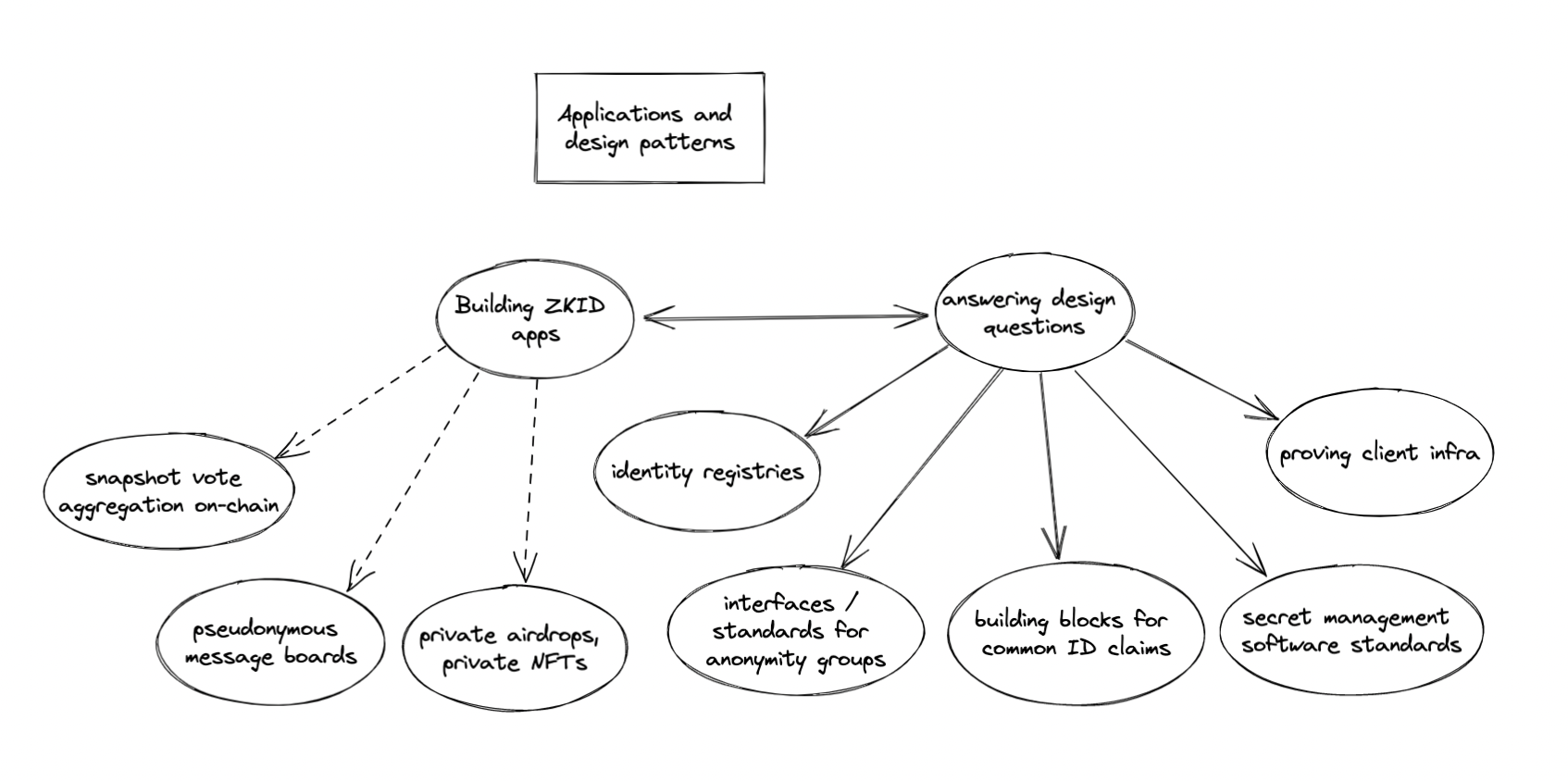

ZK Apps and Design Patterns

First off, the output of our work should be touching end users and enabling impactful production applications. In parallel with developing ZK tools and building blocks, we’ll have to figure out the best way to use and compose them. Here are a few open questions:

- What is the correct abstraction for identity? Is it an Ethereum address, a collection of Ethereum addresses, a multisig, a smart contract wallet, an ENS name, a keypair in a different cryptographic scheme, a secret biometric, a set of attestations, a higher-level construct, or something else entirely?

- What are common identity claims that people care about making? All of the above work gives us a language for making credible claims about identity; now, we have to learn how to actually speak in this language. For example, is it useful for claims to directly reference and operate on hash data stored on-chain, or is it easier if most claims are simply proofs of valid attestations by semi-trusted third-parties? Is it practical to make claims referencing historical Ethereum state in ZK proofs—and if so, what kinds of historical claims should a proving tool make easily accessible?

- What tools and standards should be expected from future ZK wallets and identity providers? For example, Metamask or hardware wallets currently support digital signing with a private key, and it is generally recommended that private keys should not be directly manipulated by users. However, ECDSA signature verification is much more expensive to perform in a SNARK than public key generation—meaning that users who wish to make ZK proofs about their ETH address will have to choose between much slower proving times (via proof of valid signed attestation) and lesser security (by copying their plaintext private key out of the wallet enclave and into ZK proof generation programs). This problem can be partially solved if wallet software eventually offers native support for ZK proof generation, which we’re currently experimenting on with the Metamask Snaps team.

- What interfaces will ZK-identity-enabled apps need to conform to? Applications both on- and off-chain will need to be designed with ZK identity systems in mind. For example, NFT-gated communities that wish to use ZK identity systems may want to also store a cryptographic accumulator of token and token owner data in the NFT smart contract, so that it is easier for users to generate claims about membership in the community. Standards for groups that we wish to make membership proofs for will need to be developed.

- Who (or what devices and environments) can generate ZK proofs? The space of viable applications looks very different depending on whether certain ZK proofs can be generated in hardware wallets, on mobile devices, in browsers, on consumer desktop computers, or only on dedicated proving servers.

The best way to answer these questions is just to start building! We hope that a robust developer community may start to form in the next few years, building applications with a variety of different approaches.

Several ZK-Identity apps can in fact be built today with the existing state of infrastructure. This is high-leverage work—beyond delivering useful applications, these projects will also inform development on tools and infrastructure. Here are some candidates for initial production applications of ZK Identity:

- Private airdrops. A common strategy for many DeFi apps is to publish a Merkle root of user addresses on-chain, and to allow users to claim airdrops by calling a function with an address published in the tree. Stealthdrop is one project from ETHUni and 0xPARC communities that adds a privacy layer to this by allowing users to claim an airdrop from any address by simply proving that they possess an attestation from some private key corresponding to an ETH address in the tree (with nullifier checks to prevent duplicate claims).

- On-chain Snapshot vote aggregation. Today, many “DAOs” use entirely off-chain voting mechanisms, where users sign votes and send these signatures to a central service provider (i.e. Snapshot) for tallying. This presents two problems: first, votes can be censored by the central authority, and past voting data can become lost or unavailable/unauditable. Second, votes are conducted publicly, leaving voting systems vulnerable to collusion. We can use ZK constructions for signature verification to “roll up” voting results into a single ZK proof of voter signatures that can be trustlessly generated and submitted on-chain. Intermediate constructions which partially distribute power from the central authority (i.e. to a wider network of attesters who post Merkle roots of tokenholder snapshots) in exchange for scalability are also possible.

- Anonymous but credible attestations. These identity tools can be used for proving membership in a group without revealing your exact identity—for example, proving ownership of a Dark Forest planet and joining an NFT-gated community without revealing your identity; making a post as an anonymous but popular Twitter user, proving that you have at least 1m+ Twitter followers without revealing your account; or proving that you’re a member of a legislature and anonymously signaling consensus in an upcoming vote. Some of these applications are discussed more in our ZK Group Signatures post.

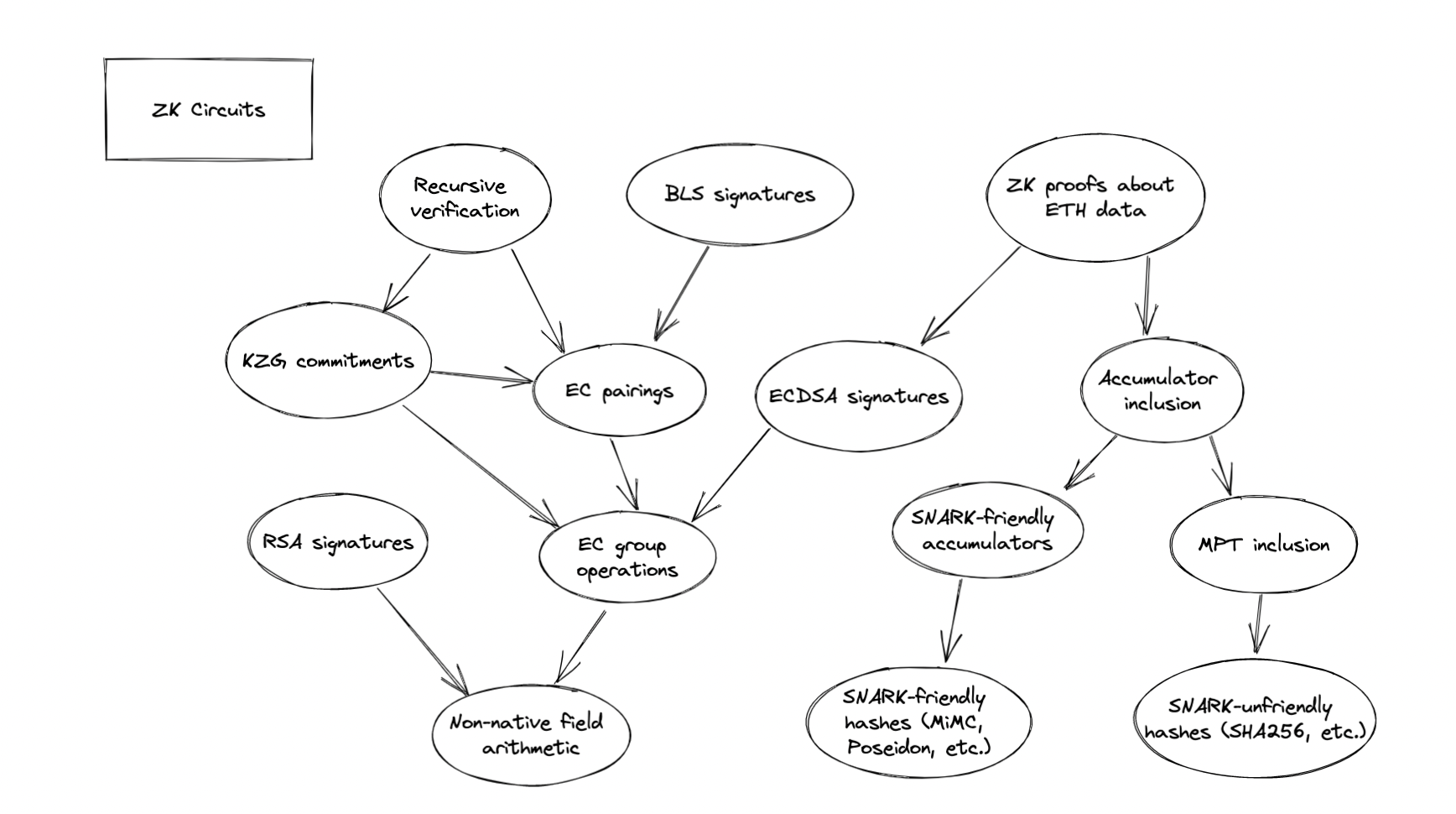

ZK Circuits for Cryptographic Identity Primitive

Stepping one level deeper in the stack, we need efficient, audited implementations of ZK circuits for core cryptographic primitives and the mathematical operations underlying them. Here is a sample of some key operations, in a very rough dependency ordering.

- Non-native field arithmetic: zkSNARK arithmetic takes place in a prime field—for example, all signals in the defaults for snarkjs are taken modulo the 254-bit BabyJubJub prime. However, cryptographic operations require us to perform operations on potentially much larger numbers—for example, secp256k1 operations require us to take the product of two 256-bit numbers modulo a third 256-bit number. The most expensive operations involved in these circuits are range checks, and one strategy for constraint optimization is to be more careful about determining when precisely we need to perform range checks.

- SNARK-friendly hash functions: Hash functions are useful in applications where users must make cryptographic commitments. In schemes where the hash function does not need to integrate with an existing standard, we can choose to design and implement hash functions that are specifically designed to be efficient in SNARK proofs. Two such functions include MiMC and Poseidon.

- SNARK-unfriendly but standardized hash functions: In many applications, we must use SNARK-unfriendly hash functions (like SHA256 or keccak) for the sake of compatibility with existing systems. For example, to prove knowledge of the private key corresponding to an ETH address, we need a ZK circuit implementation for keccak. There is lots of work to be done implementing, optimizing, and auditing these hash functions.

- Elliptic curve point addition: Elliptic curve cryptography is built on elliptic curve groups; therefore, we must build ZK implementations for the elliptic curve group law (point addition). These operations are expensive and this is one performance bottleneck for ZK identity systems; clever usage of PLONK and better implementations of BigNum arithmetic may help improve performance.

- ECDSA key generation and signature verification: ZK circuit implementations for ECDSA key generation and signature verification would allow us to build a language of identity claims that is compatible with existing ECDSA-based identity systems, such as Ethereum. Building these primitives requires us to combine implementations of EC point addition and hash functions in efficient ways.

- Elliptic curve pairing: Pairing-friendly elliptic curves give us access to bilinear maps, enabling polynomial commitments, BLS aggregate signature verification, recursive SNARK verification, Verkle Trees, and more. Efficient implementations of ZK circuits for elliptic curve pairings will unlock a huge variety of new cryptographic operations.

- Cryptographic accumulator inclusion checks: Verkle tree inclusion proofs are verifiable in SNARKs, once we have ZK circuits for polynomial commitment verification. Merkle tree inclusion proofs are verifiable today, and are practical for trees built with SNARK-friendly hash functions. MPT inclusion proofs enable us to verify light client proofs in a SNARK. In all of these cases, accumulator inclusion proof verification allows SNARKs to access data that is rolled up into a succinct commitment (”root”) of global system state—if you provide the data you’re accessing, the system state root, and a proof of inclusion as input to the SNARK, then the verifier only needs to verify your succinct proof and check that the root is correct, rather than the full system state.

- Recursive SNARK verification: Recursive SNARKs are made possible by implementation of elliptic curve pairings and/or polynomial commitment verification inside of zkSNARKs. This unlocks a new dimension of programmability and complexity in identity claims.

Circuits for all of these might first be written for R1CS (allowing for groth16 setup and proving in the near term), and in the near future optimized further for PLONK-based proving systems.

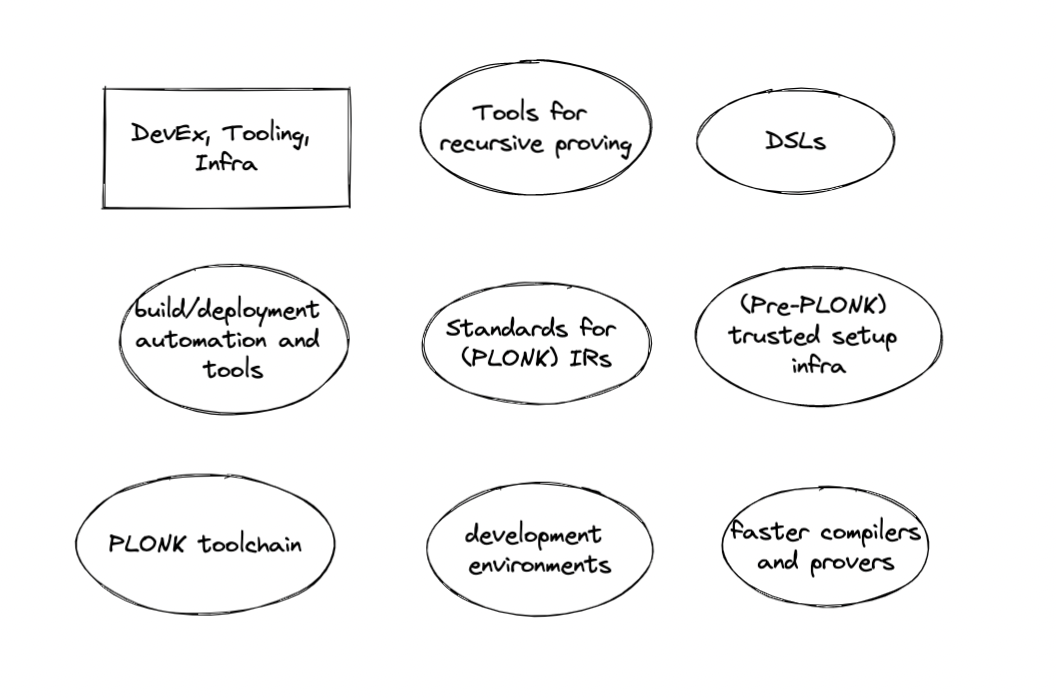

Developer Tools and Infrastructure

Developer tooling for ZK circuit engineering is an important topic. Currently, ZK developers require a relatively high level of mathematical background and technical sophistication, they must write in relatively low-level development environments, and they rely on manual effort or ad-hoc scripts to manage files and carry circuits through the development pipeline from design to production. Furthermore, the developer tooling work that has been done is scattered and fragmented among multiple R&D teams, rollup companies, and more.

Of special note here is the importance of a robust toolstack for PLONK specifically. PLONK removes the need for per-circuit trusted setup, significantly speeds up compilation and proof generation for certain circuits thanks to custom constraints, and paves the way for recursive SNARK verification. However, tooling for PLONK is currently at a much earlier stage of development than Groth16 tooling, as provers are much less optimized and support for advanced protocol features is not yet implemented in certain systems. Furthermore, much work remains to be done on standards for IRs and the design of a language for custom constraints. Groups like AZTEC, Electric Coin Co, iden3, ZK-Garage, and more are hard at work building these tools.

Beyond PLONK toolchains, here are a few active areas of work in ZK developer tooling.

- Higher-level DSLs. Current languages for writing SNARKs are very low level, and require developers to manually write constraints. We are interested in production-grade higher-level DSLs that are easier to develop in (one proof-of-concept from a 0xPARC community member) or which may even perform constraint optimizations intelligently. Additional nice-to-haves include user-defined data types/annotations, and better witness generation systems. Further down the line, DSLs that enable automation of testing, verification, or static analysis of circuits may increase our confidence in the code that we write.

- Smarter development environments. Writing, analyzing, and testing circuits is a difficult process. Syntax highlighting, detection of compile-time errors during development, IntelliSense-like tools using a combination of AST/witness analysis, annotations (i.e. marking circuit templates as “safe” or “unsafe,” flagging unconstrained signals), and shell/REPL environments may improve iteration speed rapidly. ZK Learning Group participants were sped up massively by Kevin Kwok’s ZKREPL project, which incorporates a number of the above-described features.

- Build, testing, and deployment tools; automation and pipeline management. ZK developers must currently manage ptau files, key files, build configurations, build files, and release distribution processes manually. The snarkjs tutorial currently lists 26 steps that a developer must perform to create and verify a zkSNARK, involving manual operations on over 20 files. There aren’t widely-accepted best practices for how to publish protocol parameters in a way that is accessible and auditable. Different versions of circuits must be maintained manually for different environments (i.e. turning off some constraints during testing). Tools like ProjectSophon’s hardhat-circom and Weijie Koh’s circom-helper are great first steps that help to simplify workflows drastically, but much work remains to be done.

- Common standards for intermediate representations. Different teams use different languages and tools to write ZK circuits: circom, arkworks, libsnark, and many more. Circuits written with different toolchains should ideally compile to a common IR so that generating proofs, verifying proofs, auditing protocol setups, and other common tasks can be toolchain-agnostic. For Groth16, an IR depends on a standard set of of agreed-upon cryptographic parameters and R1CS representation. For PLONK, the problem is a bit more complex, as library developers will need to figure out how to represent custom constraints and more. As an example of work in this problem space, development of a Dark Forest 3rd-party client motivated Kobi Gurkan and gakonst to write ark-circom, bridging the arkworks and circom ecosystems.

- Easier-to-use and more efficient compilers and provers. Slow key compilation and proving slows development and testing. Optimizing compilation and proving, and making libraries for these processes easy to run out-of-the-box (i.e. setting up a remote prover on a big server should be easy!) will save developers time. ZPrize is one industry initiative that aims to accelerate this work and more.

- (Pre-PLONK) Shared trusted setup infrastructure. Production-grade zkSNARK apps are difficult to launch right now because of the difficulty in coordinating trusted setup. ZCash, AZTEC Protocol, Tornado, and Semaphore all had to write customized trusted setup infrastructure. There have been some attempts to build out more reusable trusted setup tooling, but running these ceremonies is still extremely labor-intensive. Note that this will likely not be a problem in the longer term however as we move to protocols that don’t require per-circuit trusted setup.

- (Post-PLONK) Tools for working with SNARK recursion. SNARKs that support recursive verification enable us to build “programmable” SNARKs, where SNARK code could be modified “on-the-fly” by plugging in verifying keys to other SNARK submodules. Furthermore, recursive SNARKs also allow developers to parallelize proof generation. Supporting this functionality in practice is a hard problem that will likely be worked on for the next several years...

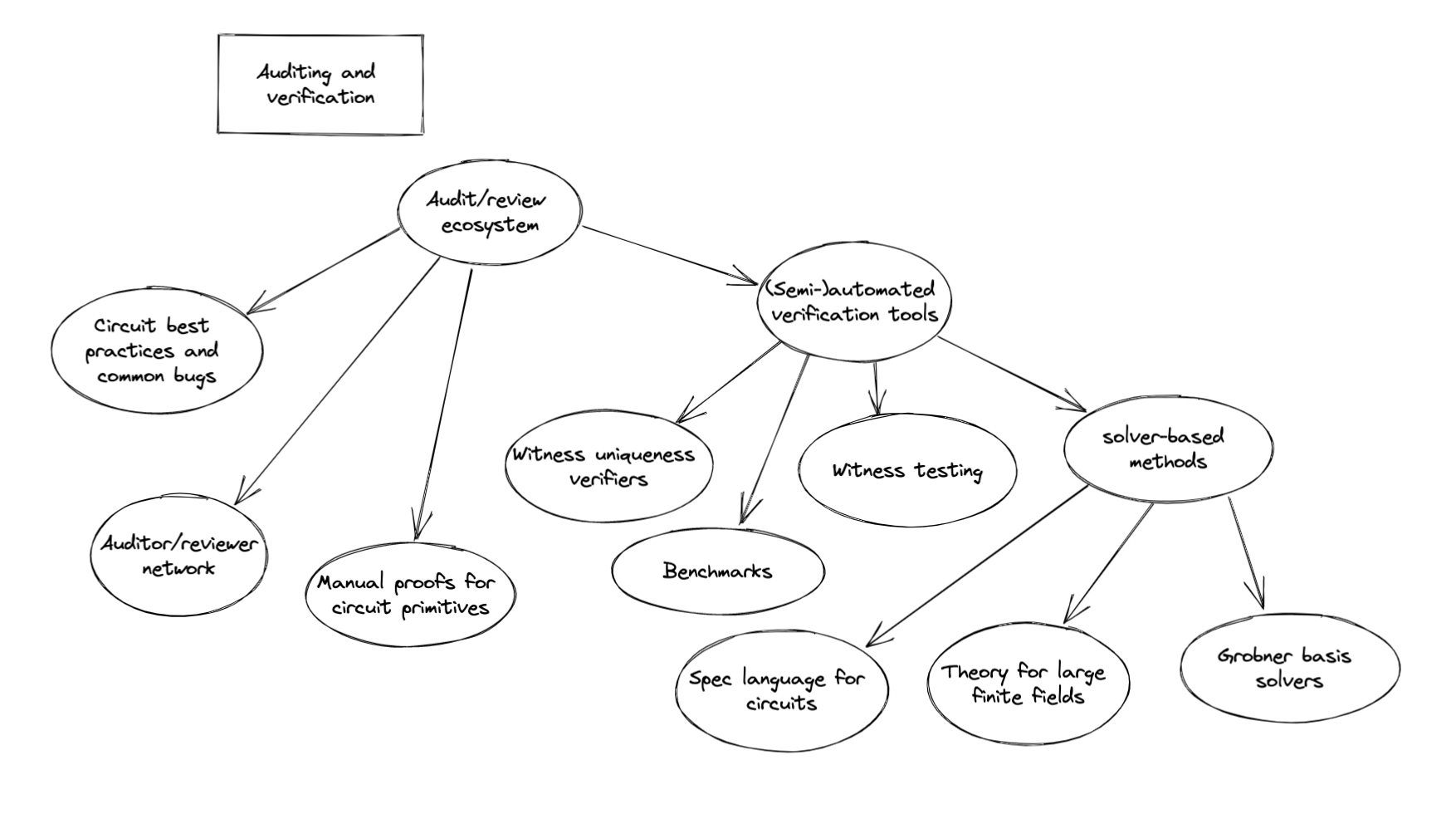

Auditing and Verification

The above-listed circuits are complex and extremely hard to verify manually. Clever constraint optimizations actually compound the problem—highly-optimized circuits are hard to reason about, and its easy to miss a constraint during implementation if you’re doing something tricky. Furthermore, it can be impossible to tell if a bug in a ZK circuit has been exploited in the wild, due to the nature of ZK applications.

It’s fairly easy to write tests that give you confidence of completeness: demonstrating that you can generate witnesses and valid proofs for witnesses properly from inputs. Gaining confidence in soundness is harder. To do this, you’d have to verify that there is a unique witness that satisfies the constraint system of a SNARK for a given input—that a malicious prover can’t substitute in a faulty witness that generates a valid proof due to a missing constraint. Even harder than this is proving equivalence of a circuit to a specification, i.e. formal verification.

Currently, the approach taken by most teams using ZK circuits in production is to commission manual, human audits, though the quality of these audits is inconsistent and the total number of people capable of performing audits is very small. We may be reasonably certain that applications like Tornado.Cash, whose circuits total only about 100 lines of circom code, are probably secure. However, our proof-of-concept groth16 ECDSA implementation relies on thousands of lines of circom code, with circuit sizes in the hundreds of thousands or millions of constraints. More complex primitives will be even harder to verify, and PLONK custom constraints will add additional complexity.

We suggest a handful of approaches for the ZK application security space. In the future, we’ll publish a blog post with a deeper overview of current approaches in this domain that we are aware of.

- Building a community of reviewers. Teams often have difficulty finding specialists with expertise with ZK application development to review their circuits and code. We can encourage existing ZK-focused teams, such as engineers at rollup companies as well as application developers, to “trade” reviews, and we can also collectively begin to train auditors.

- Establishing best practices for circuit engineering and review. As the ecosystem matures, we will want to develop best practices for building, annotating, documenting, and reviewing ZK circuits. This can be done to varying degrees—specifications in natural language or formal specs are both helpful in making circuits more legible. Enumerating common bugs and mistakes (and building some rudimentary tools for catching these) may also help both engineers and auditors.

- Manual proofs of correctness for circuit primitives. For important primitives, such as hash function or ECDSA circuits, it may be possible to manually write proofs of correctness for such primitives that can be checked with a proof checker. Other circuit builders would then be able to use these primitives with greater confidence in their correctness.

- Automated witness uniqueness verification. Ecne is the first automated R1CS witness uniqueness verifier. This project enables us to verify whether or not a ZK circuit may have any missing constraints, which is a major step forwards in building confidence in our ZK systems. We hope to support and encourage more work in similar directions.

- Solver-based methods for formal verification. Some teams are exploring automated methods for proving the equivalence of a ZK circuit with a formal specification. Efforts in this area will also require us to develop a common set of benchmarks, as well as a language for specifying ZK circuits (partially or completely).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Lakshman Sankar, Yi Sun, Kobi Gurkan, and Wei Jie Koh for feedback and review.